Computers & Competence in Canadian Government

A work in progress exploration of how our government came to struggle with technology

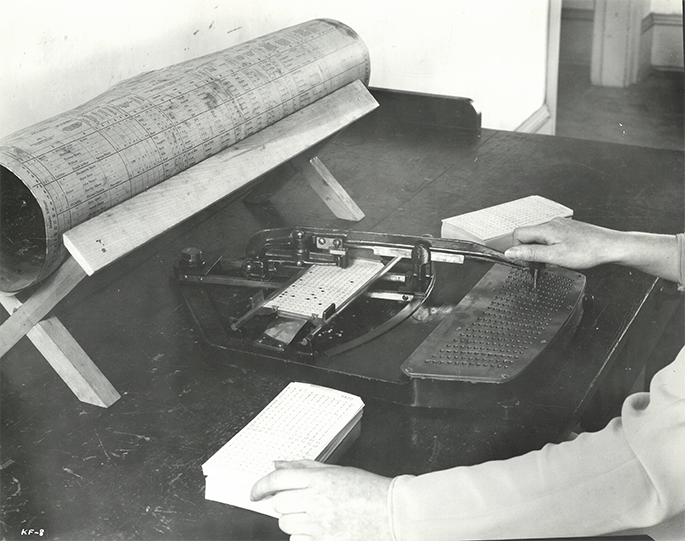

Our government wasn’t always behind the curve when it comes to adopting new technology. In the 1950s, Canada Post was an early innovator, with the Liberal government investing heavily in using computers in an urgent attempt to cut costs and manage the increasingly complex sorting that was needed to deliver mail in rapidly urbanizing areas like Toronto (source, article).

Since early computers were expensive, the earliest customers were large bureaucracies where the efficiency gains justified the high price. So in addition to subsidizing the R&D of early mainframe systems, the Canadian government was also early adopters of new technologies (Vardalas, 249).

Computers were used to tally the Census responses in 1961 (source), to do economic forecasting for the Bank of Canada (source). Through the 1960’s and 70’s computers became essential to administering the wave of new social security enhancements under the Pearson New Democrat government (Canadian Pension Plan, Guaranteed income supplement).

In the early 1990s, Canada, like many other countries, was facing significant financial pressures. This included a high unemployment rate, high inflation, and high public debt — which was about 66.6% of the GDP in 1995.

In 1994, in response to these challenges, Jean Chrétien’s Liberals followed Thatcher and Reagan’s lead in cutting down the size of government by assessing every programs’ alignment with federal responsibilities, whether they were affordable, and to identifying potential savings. Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Finance, Paul Martin, who had been appointed in 1993, was the main driving force behind these reform efforts.

With I.T. being outsourced to the private sector, there was a technology talent drain within governmental offices and departments. Initiatives to use technology continued, but internal capacity to run these programs did not increase.

In 2005, more concrete steps were taken with the introduction of the Federal Accountability Act which implemented numerous changes to procurement, including the creation of an independent procurement ombudsman. This policy aimed to improve transparency and fairness but also contributed to the lengthening of the procurement process, making it even more difficult for the government to keep pace with the rapid rate of technological progress.

In 2011, Harper’s Conservatives centralized IT services in the Canadian government under Shared Services Canada (SSC), intending to reduce costs. The Auditor General criticized the SSC for its inability to demonstrate that it was saving money, it led to increased delays, and various departments complained about the quality of service. This model of centralization, while potentially useful for standardizing practices, unfortunately had a stifling effect on innovation and agency-specific technology needs and capabilities.