Breaking Down the Rules for Better Government Technology

Over time, the amount of important stuff that we expect a modern nation to do for us has grown unimaginably big. If it surprises you that in Canada, the US and probably other G7 countries the Federal government is the single largest employer 1, I encourage you to notice how nearly every important service we receive is connected to the work provided by our civil service. To me, the fact that we take the vast majority of this stuff for granted suggests that, overall, our government is quietly and successfully doing all the jobs that we as citizens expect it to.

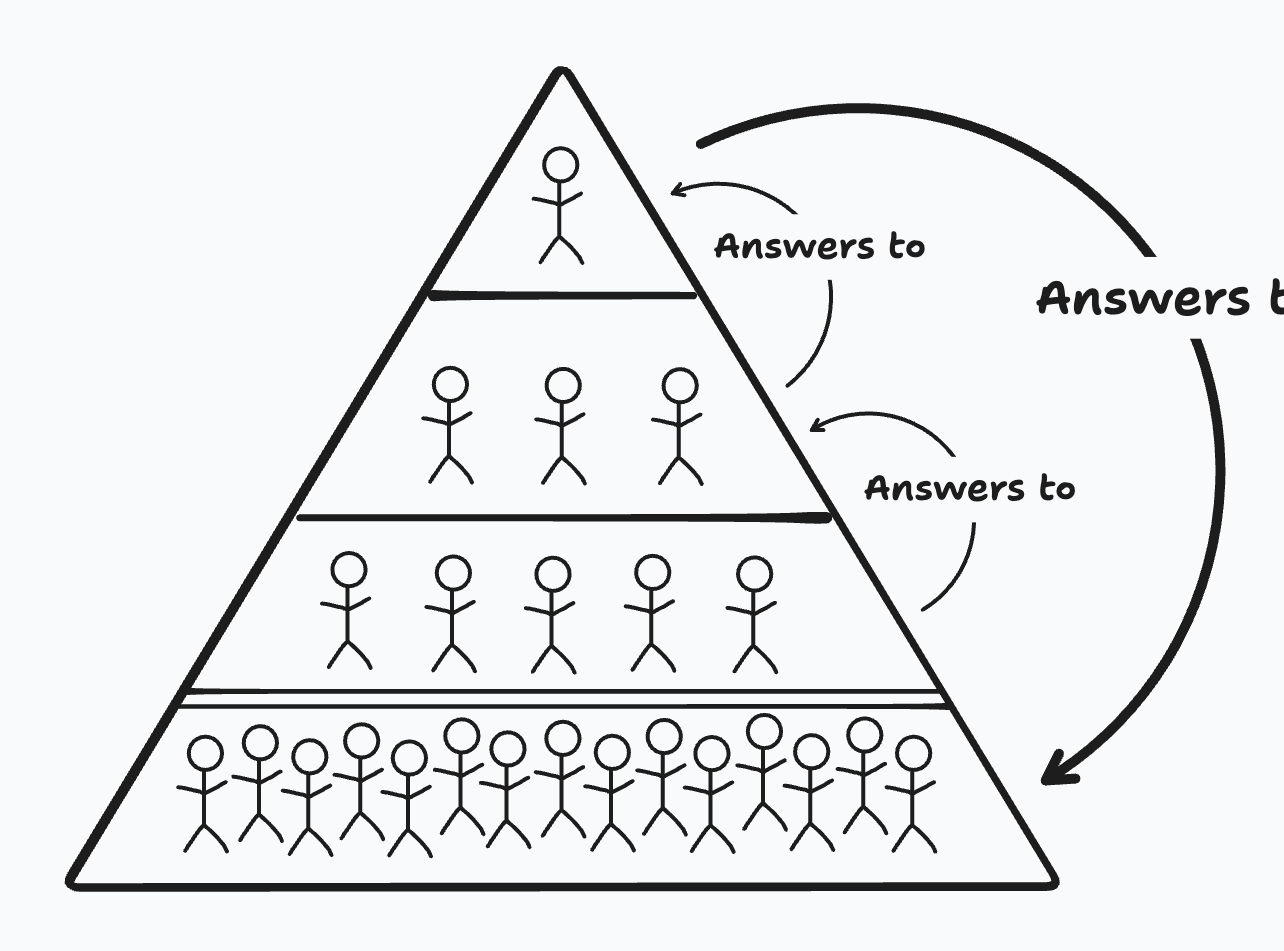

In liberal democratic countries like Canada, it’s the executive branch of our government that’s responsible for actually doing all the work that’s been written into law by our elected representatives. We typically think about the executive branch as faithfully carrying out the will of the people, and the best solution we’ve come up with to scale this up is with a strict hierarchical bureaucratic organization where direction is set from the top down.

When things go wrong, accountability cascades back up the chain of command, so that the people with the most authority have an incentive to closely monitor and direct their subordinates. This type of setup is held together by a vast set of rules in the form of laws, bylaws, regulations, orders, or directives, guidelines, SOPs. From this lens, it’s intuitive that if we want to prevent corruption, favouritism, and political bias, we’d need rules aimed at limiting the discretion of civil servants to make their own decisions.

So if this system works so well and has accomplished so much, why is it that we get repeated failures of the government in specific areas like buying technology solutions? From the Obamacare rollout in the US to Canada’s failed (and still failing) 2011 Phoenix pay system, and most recently the ArriveCan app. Are we lacking enough oversight or rules for how we buy tech? Do government employees have too much discretion to just spend tax dollars how they want?

If governments are so good at making rules, how come we keep failing to spend money responsibly on technology projects?

When all you have is a gavel, every problem looks like a rule violation

As many experts pointed out1, the continual stream of bad outcomes is not surprising because it’s not the lack of rules that causing the problem, it’s the excess of rules.

In the case of ArriveCan, the overwhelming number of rules aimed at limiting discretion when building technology combined with the urgent need to actually get stuff done quickly during a pandemic made this outcome highly likely. When the “unstoppable force” of a government’s urgent priorities hits the immovable book of of rules that prevents actions, the money will inevitably flow towards people a reputation for “getting things done” expediently no matter what the cost. To me, the existence of this sketchy consultant industry is a byproduct of government’s systemic reaction of rule-making as a knee jerk reaction to public outcry.

The Procurement Practice Review of ArriveCAN already notes that in response to the rules not being followed they’re adding more rules to address the rules that weren’t followed. When you read the report, its internal logic is actually compelling and intuitively makes lots of sense; if people found ways to skirt around the rules, then we need stronger rules and enforcement where those things fell short.

But we easily can see the dilemma when we zoom out: we’re caught in a systemic failure to create accountability, but the tool we’re using to solve it is recreating the problem. From the traditional top down mindset it might feel like we either have to choose between more accountability but with rules that slow things down, or less rules, more discretion, and higher risk of abuse and waste. There is the sense that “one person’s red tape is another persons due process” 2.

I believe this is a false dilemma. If we want to fix the way government buys technology, we need to look at the whole system and rethink what discretion and accountability should look like.

The first way we should adjust our mindset is to face the reality that creating rules has fundamental limitations in limiting employee discretion. In The Machinery of Government: the Ethics of Public Administration (from which many of these ideas originate), Joseph Heath examines ethical basis for relying on discretion in government as well as the risks of trying to eliminate it.

Firstly, he points out, eliminating discretion is impossible and counterproductive:

De facto discretion often arises as a perverse consequence of attempts made to limit it. Discretion is sometimes like the proverbial bump under the carpet—it can be moved around but not eliminated. In other cases, the attempt to limit discretion winds up increasing it. 3

Heath points to several common situations where the rules aimed at limiting discretion invariably lead to failure, which I’ve applied to the context of government technology procurement (a.k.a. the way government buys technology):

- Runaway rules

There can be a sort of cascading failure when using rules to limit discretion. To avoid favouritism or corruption, many procurement departments traditionally set up rules requiring them to take the lowest bid for a project. This inevitably leads getting stuck with unrealistic bids from vendors who are unable to deliver on time, or at high quality. So the common practice is to then add rules requiring pre-qualification to ensure that only vendors who are qualified to do the type of work can apply for bids. This tends to cut down the pool of applicants to sophisticated larger firms who can carry the upfront costs and uncertainty of the process. It has also created a profitable niche for small consultants who specialize in winning these contracts then applying much looser rules to subcontract out the actual work. The rules also disincentivize vendors from delivering good work because they cannot then rely on any goodwill from past successes factoring into future procurements.

To ensure good results within the limits of these rules, savvy bureaucrats will carefully craft application criteria so that only their favoured vendor meets the requirements and others will be dissuaded. So another rule is added that over a certain budget threshold, projects must have a certain number of qualified applicants. But a savvy bureaucrat can then split the project into multiple smaller projects that fit under the limit. Rules can then be imposed to prevent contract splitting. Just like a lump in the carpet, these rules on procurement don’t eliminate discretion, and it may be tempting to add “just one more rule” to resolve the problem, but each layer of rules actually undermines the chances of a good outcome.

- Conflicting rules

In cases where rules have proliferated and accumulated in this way, it’s common for there to be contradictory rules. In systems where dozens or hundreds rules have been added to add more oversight, decision makers actually find themselves in a position where they get to choose which rules should apply. A simple example is procurement rules that don’t appreciate the iron triangle of project management, sometimes expressed as “You can have it good, fast, or cheap. Choose two”. Rules that invariably require all three inevitably set up decision makers to use their discretion even if, on paper, all three criteria are required (the ArriveCan app is probably an extreme example of this). In modern software development, this problem is largely solved by allowing project scope to be variable while keeping quality and timelines fixed, but traditional government procurement requires vendors to bid for a fixed scope of work.

- Inadequate resources to enforce rules

The more rules a system has, the more effort is required to enforce them. It’s incredibly common for whoever is responsible for enforcing the rules to have inadequate resources to do so. Whoever is responsible for enforcing the rules then has to use their discretion about which rules are most important and how they choose to enforce them. This happens in procurement as well, but a classic example would be tax auditors and police, who have no chance of enforcing all the rules and therefore have to use their discretion. Another example would be means-tested benefits.

- Impossible to supervise

There are many types of work where we’d want people to follow a set of rules but the nature of the work is inherently difficult to supervise. A huge proportion of required documentation and reporting falls under this umbrella. Although reporting procedures can encourage adherence to a given process, whenever the reports aren’t independently verified (or verifiable), it becomes an exercise in “box checking” where the only thing really being confirmed is that the reporting procedure was followed, not the underlying rule. This is why there are frequently large IT projects that are delivered with functionality that is clearly low quality despite a labor intensive formal quality assurance reporting process being met. [The solution is to test for outcomes - demo working software, not adherence to process rules]

- Inadequate resources to deliver

It’s very common for government to be responsible for delivering benefits or services for which there is not enough to go around. In public housing, for example, it is common to use queues and eligibility criteria to triage housing units for those who need them the most. Even when the rules around these are strict, budgets grow or shrink the amount of resources over time and front line staff inevitably use discretion to decide and prioritize on a case by case basis. So while the formal rules may assume a uniform process is followed, front line workers may be forced to use their discretion to interpret what decisions best accomplish the bigger objectives. 4

So we can see how self defeating it is to try to create accountability by creating rules limiting discretion. But we’re still left with the question of how we create accountability and scale it across an organization with hundreds of thousands of people.

There are no silver bullets. The amount of scrutiny that can be applied from the top of the bureaucracy down is is limited. It’s also hard to expect regular citizens can apply accountability across the entire government. For example, transparency laws are a good approach that enables more bottom up accountability to the public. Freedom of information requests, for example, can be beneficial in enabling citizens to have insight into their government. But they often fail the same way as other rules: they add more work for people who are willing to follow the rules, and are easily bypassed by people who aren’t.

A more helpful starting point may be to recognize that in an organization with 100s of thousands of people, the vast majority of decisions are already left to discretion, and civil servants mostly make good use of their discretion. Culture, circumstance, and incentives are a much bigger factor in decision making than explicit rules. Heath gives the example of the police: with thousands of laws to enforce, police inevitably have a lot of discretion to pick and choose what gets enforced. However, within a given jurisdiction, the norms and values of the department and expectations of colleagues make those decisions relatively predictable.

This points to a promising area to focus on if we want to improving outcomes and accountability: the hard work of shifting internal culture via onboarding, education, mentorship, setting institutional norms, internal incentives, mindsets, and values.

If we want government to deliver technology solutions that meet the expectations of the public, an excellent workplace culture, expertise, and a strong public sector ethos are not just important details to consider after we perfect our procurement rules. These things are necessary for building the trust that’s required for employees to be empowered to make decisions, and to remove the tangle of rules that makes their job more difficult.

Footnotes

-

Please correct me if I’m wrong but some searching put Federal level employees at 357,247 vs 220,000 for Weston and the US is 2.79 million civil Federal service employees vs. [1.6 million at Walmart](1.6 million) ↩ ↩2

-

The Machinery of Government: the Ethics of Public Administration, Joseph Heath ↩

-

Ibid ↩

-

This is why “rules as code” often doesn’t work - because the rules are not adaptable to local knowledge. One report on rules as code found: “Caseworkers use relationships and knowledge to help people get support. They wondered if Rules as Code could optimize bad policy that is designed to keep people from receiving benefits. Similarly, a grassroots practitioner highlighted potential equity implications of further automation, and how to account for the “fuzziness” of rules that can be interpreted to help people receive benefits. This practitioner asked a foundational question: “Can we develop standards to facilitate automation while also keeping human discretion in the loop?” ↩