Are we Pulling the Right Levers on Digital Transformation?

A question I’ve thought about a lot is how to focus on the biggest levers for change in how Canada approaches technology initiatives.

As I wrote about previously, software delivery in government is a complex system and if you pull on the wrong lever when trying to fix something, you can actually make the problem worse. The key example I focused on was how the government’s overuse of traditional policy driven “rule-making” approaches actually leads to worse outcomes.

So what are some better ways to tackle these problems? If you want a concrete list, Amanda Clarke and Sean Boots have given excellent recommendations that are very well substantiated. This article is a more abstract exploration about what the highest leverage focus areas might be. To guide this, I’m using infamous systems thinker Donnella Meadows’ advice on finding high leverage points for change within a system. I’ll be referencing her book Thinking In Systems: a Primer, but (here is a good summary of the work).

The Service Delivery System

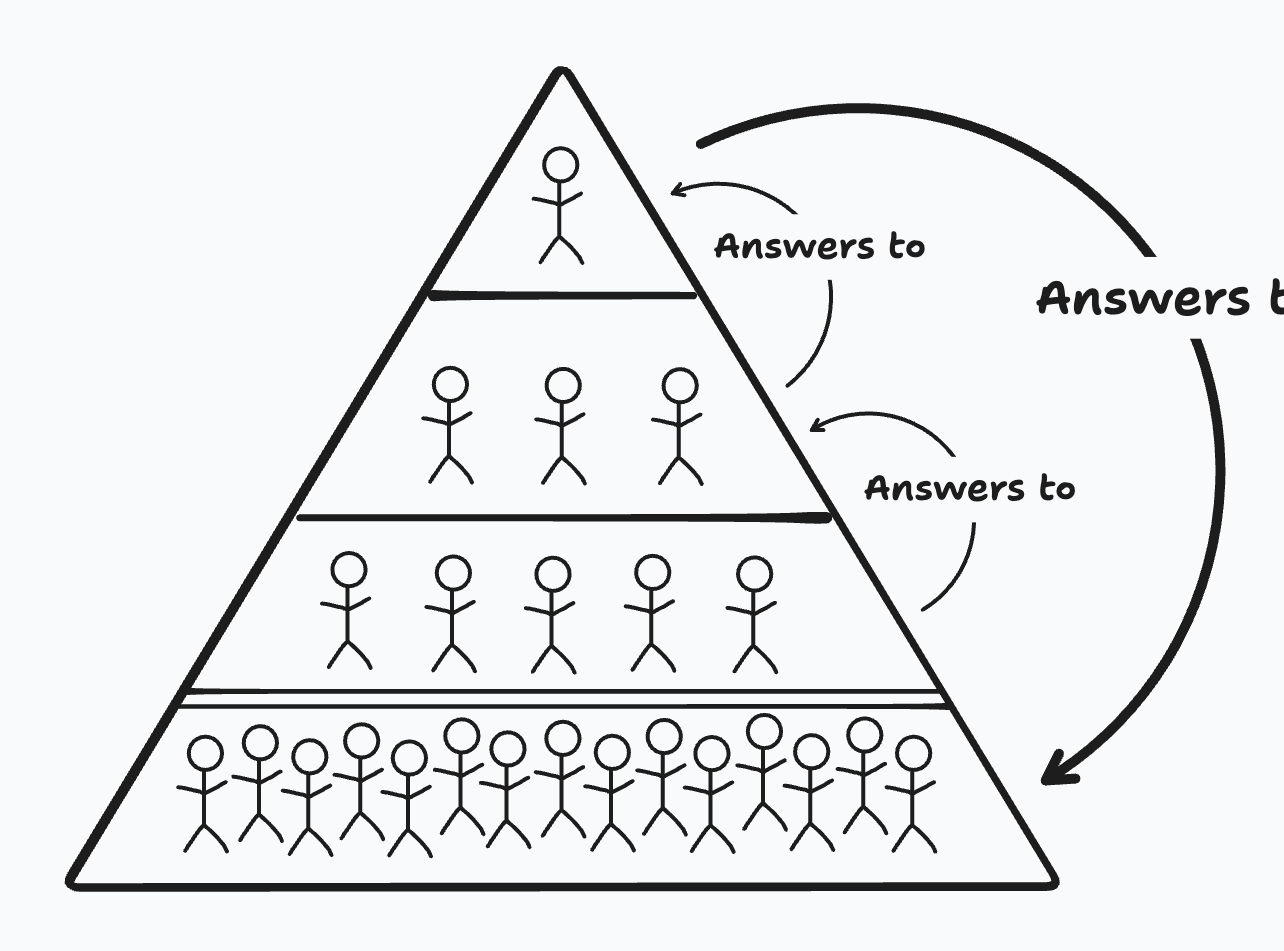

First, let’s sketch out the system in broad strokes to give us an idea of how it works and where the levers even are before we start pulling on things. In the spirit of “All models are wrong, but some are useful”, here’s how governmental digital initiatives work:

The inflows of the system are a) money and b) the direction on how to spend it: residents put in money (via their taxes) along with their priorities (via elected representatives), and representatives give direction and oversight to the executive branch which is accountable for creating and administering services. In this case, the “outflow” we’re focused on are the digitally enabled services that residents receive.

The public’s trust in this system is determined by the perceived quality of the services they receive, based on the money and input on priorities they’ve given. As a result, if residents perceive that the service does not meet their expectations, they will put pressure on elected officials to put pressure on the executive branch until expectations are met.

As an aside, something notable in this model is that the perceived quality of the service could be affected by a range of things beyond the service itself: the increasing rate of change of technology, people’s rising expectations due to comparable services in the private sector, shifting priorities of the public, the perceived value of individually vs collectively purchased services, etc.

There are of course more intricacies, including multiple feedback mechanisms exist to push the system to meet resident expectations (each with varied delays and effectiveness): Public pressure, legislation, bureaucratic rulemaking at each level of the hierarchy, budget changes, changes to staffing, changes to organizational structure, and sometimes, rarely, direct feedback from service users.

Given this rough model of government service delivery, how might we intervene to ensure that service quality meet the public’s expectations?

The Levers

In what follows, I’ll list Meadows’ 9 recommended leverage points which she ordered from least to most effective, along with some notes on how these apply to software delivery in the Canadian federal government ecosystem:

12. Constants, parameters, numbers (subsidies, taxes, standards).

People care deeply about parameters and fight fierce battles over them. But they RARELY CHANGE BEHAVIOR. If the system is chronically stagnant, parameter changes rarely kick-start it. If it’s wildly variable, they don’t usually stabilize it. If it’s growing out of control, they don’t brake it.

One of the least effective ways to improve the quality and cost of government digital services is to change the amount of funding going to an initiative, without changing anything else. This may seem surprising to some, but we’ve seen time and time again that huge mega budgets don’t lead to better outcomes.

11. The sizes of buffers and other stabilizing stocks, relative to their flows.

In this case, if we think about perceived quality of digital services received, one thing that could help with perceptions would be if residents had more trust in the public service. A larger reservoir of trust could stabilize the system against short-term failures or negative perception of the value received. For example, if journalists weren’t frequently sharing stories of government wastefulness, it’s less likely that the public would perceive that they weren’t receiving the services they wanted.

There’s no doubt that more trust would have a big impact, and there is definitely a need for our institutions to rebuild public trust. Anyone who has worked in government knows that fear of bad headlines can push public servants to play it safe instead of taking risks and trying new approaches. A healthier media environment with more nuanced discussion could help with that.

However, increasing the public’s trust is not an easy lever to pull on: it can only be increased commensurately with actual service quality improvement. Unfortunately, we can’t waive a magic wand and manifest blind trust without also removing a crucial feedback loop that is needed to encourage service improvement.

10. The structure of material stocks and flows.

In the model I outlined, there are a lot of people as well as physical infrastructure in place to help deliver a service. It’s a big machine and there’s a lot that needs to be improved:

- Modernizing IT infrastructure to move off defunct mainframes and support more rapid deployment and scaling

- Implementing shared digital public infrastructure to standardize identity management and data access

- Improving the talent pipeline by creating dedicated technology hiring programs within the public service

We could make a much bigger list of these types of structural improvements (and these things absolutely DO need to get done) but the reason Meadow’s lists these as lower leverage is that they are crucial but not quick, cheap, or easy to change. These types of changes need long, sustained effort over multiple years and changes in political leadership.

9. The lengths of delays, relative to the rate of system change.

I would list delay length as a high leverage point, except for the fact that delays are not often easily changeable. Things take as long as they take. You can’t do a lot about the construction time of a major piece of capital, or the maturation time of a child, or the growth rate of a forest.

Meadows argues that the amount of delay in a system’s feedback loop can be effective, but is often hard to change.

This is true at higher levels of the system: passing laws, adjusting budgets, and changing policies is a long process, and changing priorities too quickly before changes can even be implemented does not actually help.

On the other hand I’d argue that digital service delivery is a bit of a special case here, because small changes can be done quickly and continuously.

Decreasing the delay between when a service starts being built and when it receives public feedback would considerably improve quality, and this delay is so long right now that I’m not even a little bit worried of it becoming to frequent.

In software, giving a demo of working software sooner is a reliable way of improving a product. In a similar vein, in procurement, ending contracts with vendors that don’t demonstrate frequent progress can save tons of money. The only limitation to using this lever right now is only for legacy systems that can’t keep pace with modern development cycle times.

8. The strength of negative feedback loops, relative to the impacts they are trying to correct against.

A negative feedback loop slows down a system’s process in order to maintain homeostasis. “…humans invent them as controls to keep important system states within safe bounds”.

In this case we can think of all the cases of literal regulation, or rule making, as one type of negative feedback loop that keeps the system running smoothly. The corpus of rules in place to prevent corruption and transparency to the public are how we ensure that we get what we pay for. But as mentioned earlier, there are limits to this approach:

The “strength” of a negative loop — its ability to keep its appointed stock at or near its goal — depends on the combination of all its parameters and links — the accuracy and rapidity of monitoring, the quickness and power of response, the directness and size of corrective flows. Sometimes there are leverage points here.

The ability to correct from failure is critically important. A timely, precise, and proportionate response to a service delivery failure can be highly effective. I’d even argue that, overall, rulemaking in this way has made liberal democracies an extremely effective way to deliver services that residents collectively want. But overuse of rules as a feedback mechanism has made them increasingly disconnected from the outcomes intended by those rules. The way they are currently used, they frequently disincentivize failure in a subtle but critical way: because of fear of failure at multiple levels of the hierarchy, people use “following the rules” to hide failure rather rather than correct it.

Luckily, there are other, more effective feedback mechanisms to keep service delivery in check. Modern practices like user research, iterative development with weekly demos, beta testing, and staged rollouts can catch assumptions and potential failures in a direct, actionable way before they get “too big to fail”.

7. The gain around driving positive feedback loops.

Contrary to how the name sounds, positive feedback loops are not always a good thing.

A negative feedback loop is self-correcting; a positive feedback loop is self-reinforcing. The more it works, the more it gains power to work some more. … Positive feedback loops are sources of growth, explosion, erosion, and collapse in systems. A system with an unchecked positive loop ultimately will destroy itself. That’s why there are so few of them.

It seems like these are more rare in a slowly changing system like government, but consider again the erosion of trust in government’s ability to deliver. The case of ArriveCan demonstrates the case well.

The inability to meet resident expectations puts pressure on political leaders who then put pressure on the executive branch, who put pressure on policy makers to put more rules on civil servants, who then have less discretion than they need to deliver services that meet resident expectations. This complex chain of events is self reinforcing and creates a vicious cycle that is demoralizing and self-fulfilling.

There may be ways that leaders within an organization can mitigate this cycle, but lowering the gain on this feels like a bandaid solution, and as we’ll see, the real solution would be reversing the cycle completely.

6. The structure of information flows (who does and does not have access to information).

This one is intuitively important: if the issue we keep circling is the multiple levels of hierarchy in the feedback loop, then restructuring information flows can be a quick and powerful leverage point. We can more effectively fix the discrepancy in service expectations vs. reality with better information flow between the people actually delivering the service and the public (as well as their representatives). This is why “working in the open” has been a core tenet of the civic tech movement.

Examples of working in the open include:

- Making code repositories public for cross-governmental reuse and input

- Regular, accessible reporting on project progress including celebration of positive outcomes

- Establishing channels for ongoing user feedback

5. The rules of the system (such as incentives, punishments, constraints).

Changing the incentives, punishments, and constraints can jolt the system out of the vicious cycle it is stuck in. There’s no reason we couldn’t have a culture that celebrates good outcomes instead of just rewarding adherence to rules. Making this change is by no means easy, but in many ways, these changes are much easier than many of the interventions listed above.

Examples of this type of intervention include:

- Shifting from rigid, one-size-fits-all procurement rules to more flexible frameworks that incentivize trust building rather than box-ticking

- Implementing outcome-based performance metrics for digital initiatives

- Moving away from punishing risk taking to celebrating and rewarding early failure and rapid learning by civil servants

4. The power to add, change, evolve, or self-organize system structure.

Underlying the movement away from process and rules based incentives there is a pre-requisite to give civil servants more discretion in how they do their jobs. Political leaders can dictate the “what”, but “how” service is delivered should be up to the people delivering the service.

I covered this in detail in the previous post, but I’ll highlight one specific aspect here: the ability to experiment, fail, and learn in order to evolve is a crucial requirement for delivering modern digital services. It is also really difficult:

Self-organization produces heterogeneity and unpredictability. It is likely come up with whole new structures, whole new ways of doing things. It requires freedom and experimentation, and a certain amount of disorder. These conditions that encourage self-organization often can be scary for individuals and threatening to power structures. As a consequence, education systems may restrict the creative powers of children instead of stimulating those powers. Economic policies may lean toward supporting established, powerful enterprises rather than upstart, new ones. And many governments prefer their people not to be too self-organizing.

Making this shift is incredibly difficult culturally, but relatively minor interventions like building teams that are cross-functional and have decision making authority are very straightforward and achievable.

3. The goals of the system.

Traditionally, the executive branch has been all about executing projects with a fixed, predetermined scope on time on budget. The “goal” is seen as collecting requirements up front and delivering a finished product.

This approach works for building a bridge, but not a service that needs to be responsive to changing public expectations. Modern technology organizations build permanently funded products that are staffed for learning and growing over time. These products still have budget and time constraints, but instead of spinning up projects and calling it a day, there is an underlying assumption that the underlying service and products need to continuously improve over several years. This means there is less pressure to solve every problem in one go.

2. The mindset or paradigm out of which the system — its goals, structure, rules, delays, parameters — arises.

From what I’ve seen, the most common mindset in government right now (especially at the Federal level) is fear driven: avoiding bad headlines is a strong incentive because it activates the organization’s immune system to make more rules.

We need to shift to a mindset that empowers all levels of the bureaucracy to be accountable for customer satisfaction. Successful companies trust and empower their front line staff and value their proximity to customers as an important feedback mechanism. Rather than shielding public servants, we should follow the same approach.

A fear driven mindset makes sense if you see the system as a top down hierarchy, driven by rules and punishments. If leaders see their roles as supports and they can learn to empower and trust the teams actually doing the work of delivering services, the mindset can be shifted.

But there’s one step that a leader would need to think about in order to make this shift.

1. The power to transcend paradigms.

I believe the dynamic where political representatives hold the executive branch accountable incentivizes a fear of the public that kicks off a negative spiral.

I think Audrey Tang points to a new model that flips the old paradigm on its head:

Instead of trusting the government to make good use of public resources, the government instead trusts the civil society, trusts the entire society to make good use of the shared common data.

The current structure of how we deliver services has done a pretty good job, historically. It is built on a certain mechanism of accountability, but it doesn’t incentivize trust building. The executive branch needs to trust the public enough to bring them into service delivery. We need to start viewing citizens as co-creators of public value, not just service recipients.